Don’t let the Darko Entertainment logo fool you if you ever

have the misfortune of seeing God Bless America. If you’re

a wannabe film buff ages 24–35, Donnie Darko is probably

your favorite movie. And though its status as a cult classic forced the film

into the uncanny valley

of popularity, at which point it becomes too popular to be cool, you can’t be

blamed for digging Darko or for

making the mistake of assuming that seeing a Frank the Bunny logo in

the opening credits of a film signals an auspicious start.

If God Bless America

is any indication, the Darko Entertainment logo might as well include a tagline

that warns, “Facepalm all ye who enter here.”

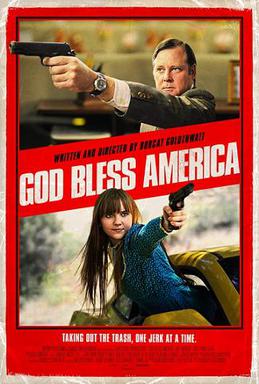

A miserable, 105-minute harangue about the evils of media,

reality TV, celebrity culture, and—wait for it—rudeness, God Bless America follows Frank, a disillusioned insomniac who gets

fed up with American culture and his annoying peers and goes on a killing

spree. You can’t miss the takeaway message in God Bless America, because Frank’s countless soliloquies about the

shallowness and inconsideration of Americans and media are about as subtle as

an icepick in the eye. Obviously, we all hate noisy neighbors, teenagers who

talk through movies, and the abusive voyeurism of reality TV. But this film is

so heavy-handed and obnoxious about teaching these lessons that Frank ends up

coming across more like a cantankerous grump who doesn’t understand the noisy

music and tweets that those youngns are always talking about these days than a

cultural-war hero.

God Bless America

is a pathetic attempt at being both Natural

Born Killers and Network. But

unlike the Oliver Stone and Sidney Lumet films that God Bless America wants so desperately to be, the Bobcat Goldthwait-directed

movie’s distain for salacious media isn’t punctured by any thoughtfulness,

theoretical insight, or any gesture toward subtlety.

The film starts with an admittedly funny montage of faux

reality shows that Frank watches late at night when he can’t sleep. These scenes

are the only few minutes of the film that are worth watching. Because even

though the shows-within-a-movie perpetuate the idea that women are catty,

fame-hungry bitches who can’t get along with each other, one scene includes a

catfight in which one woman takes out her tampon and throws it at another woman

for shitting in the first woman’s food. In another redeeming daydream sequence,

Frank skeet shoots a baby.

After being diagnosed with an apparently fatal tumor and

being fired from his job, Frank starts acting out these murderous fantasies. He

starts by hunting down a spoiled reality TV star and ends by targeting the

judges from an American Idol-type

show. So obviously the film is trying to convince us of the evils of media. But

this message gets mixed up when Frank eventually expands his targets to

basically anyone who is rude or who ends up on the wrong side of his pet

peeves. This message is further blurred when we see that Frank clearly desires

media coverage of his antics and when he takes a break from killing to go to a

movie theater to watch a documentary on the Mai Lai Massacre. During

the movie, Frank himself massacres some teenagers who were talking loudly.

We’re supposed to be on Frank’s side because he’s punishing the obnoxious

people that we’re powerless to stop in public. But in the logic of the diegesis,

he’s watching (and apparently appreciating) a film that is deeply critical of

senseless, mass killings.

These muddled moments speak to the larger problem in God Bless America. For a film that tries

so hard (like, Waylon Smithers

hard) to not only make a profound statement about culture but also to

symbolically work against it through Frank’s cathartic killings, the film ends

up reinforcing the same stereotypes and values that it explicitly positions

itself against, especially misogyny.

In Frank’s first big soliloquy—there are probably a baker’s

dozen throughout the film—he chastises his co-worker for being a fan of a

“shock jock” who is clearly modeled after Howard Stern. When explaining his

aversion to the radio personality, Frank says that he doesn’t tune in to the

show because he doesn’t hate people who have vaginas. So he’s aligning himself

with feminists who view Stern and his ilk as some of the most loathsome misogynists.

At this point, the audience could rally behind Frank. He’s

on the right side of a good cause. After all, media objectification and hatred

of women is a well-documented social ill. But Frank’s passion about this

particular cause is puzzling since the film goes on to villainize, violently

punish, or sexualize every woman Frank comes across in his personal life and on

TV.

First, there’s the woman secretary who doesn’t share Frank’s

affection. She actually sets Frank’s rage in motion in a scenario that

completely dismisses and delegitimizes the problem of sexual harassment in the

workplace. We’re supposed to side with Frank when he gets fired for looking up

the secretary’s home address—work files—to send her flowers. While that’s

probably not a fireable offense, the film treats the secretary’s anxiety over

Frank’s gesture as reactionary, politically correct, and ungrateful. But unless

you think that the long-standing, all-too-real problem of men sexually

harassing women at work just boils down to bitches not knowing how to take a

compliment, you could see the situation for what it really was. Frank was a

creepy flirt who mistook the secretary’s graciousness for romantic interest.

Given his propensity to go on a killing spree, the secretary probably sensed

that he was a little off. Imagine if, instead of sticking to friendly greetings

and book swaps, your off-kilter colleague looked up where you live in files that

are supposed to be confidential to do something that leaped over several levels

of appropriate acquaintance behavior. It would freak you out, too.

There’s also his ex-wife, who treats Frank callously when it

comes to custody issues with their daughter, who is just as much a spoiled,

horrible brat as the My Super Sweet 16-ish

reality star who ends up being Frank’s first victim. And, of course, how could

we forget his Lolita-ized sidekick.

Roxy the sidekick is played with about as much panache as

you might expect from a

former Disney star trying to build indie cred. She seems to revel in her pseudo

badassness when she delivers such gratuitous and ineffectual lines as “You look

like fuck pie, Frank.” And her contributions to Frank’s holy war are mostly to

suggest much more shallow targets (people who give high-fives or who misuse “literally”)

than Frank’s more seemingly righteous ones (a Glenn Beck-type pundit and the

Westboro Baptist Church congregation). She also proves that women are liars

when we find out that she’s not all she seems, and she helps bolster Frank’s uprightness

by repeatedly and unsuccessfully trying to seduce him.

Really, everything above is only the tip of the iceberg of

suck. There’s the crappy production, the incongruous music choices, the bizarre

aesthetic tangents, and one insanely, unnecessarily long gun-buying scene that seems

to only exist because the guy playing the gun dealer is someone important’s

BFF. This is an unfunny, politically limp movie that is trying its damndest to

be edgy and important. But ultimately, it’s a very familiar message: An ineffectual

white dude overcomes the bitches in his life and acquires phallic power to

claim the respect he believes he’s entitled to.

Bechdel

Test: Probably fail. I hate this movie way too much to go back and check.

Overall Grade: F, F, a million times F

Feminist Grade: See overall grade.